Artistic gymnastics

is a discipline of gymnastics. Competitive gymnasts perform short routines (ranging from approximately 30 to 90 seconds) on different apparatus, with less time for vaulting (see lists below). Artistic gymnastics has become a popular spectator sport at the Summer Olympic Games, and in numerous other competitive environments. The related discipline of general gymnastics is geared more towards participation for fun and fitness, rather than competition, and attracts a respectable number of participants including retired gymnasts.

The competitive gymnastics are governed by the Federation Internationale de Gymnastique, or FIG. The FIG designs the Code of Points and regulates all aspects of international elite competition. Within individual countries, gymnastics is regulated by national federations, such as BAGA in Great Britain and USA Gymnastics in the United States.

Gymnastics as a system of harmonious sports training originated in Ancient Greece more than 2,000 years ago, although gymnastic exercises and even some sort of apparatus were used in the ancient China and India for medical purposes much earlier. The system was mentioned in works by ancient authors, such as Homer, Aristotle and Plato. It included many disciplines, which would later become separate sports: swimming, race, wrestling, boxing, riding, etc. and was also used for military training. In its present form gymnastics evolved in Germany and Czechoslovakia in the beginning of the 19th century, and the term “artistic gymnastics” was introduced at the same time to distinguish free styles from the ones used by the military. A German educator Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, who was known as the father of gymnastics , invented several apparatus, including the horizontal bar and parallel bars which are used to this day. Two of the first gymnastics clubs were Turnvereins and Sokols.

In 1881 International Gymnastics Federation was founded and remains the governing body of international gymnastics since then. It included only three countries and was called European Gymnastics Federation until 1921, when the first non-European countries joined the federation, and it was reorganized into its present form. Gymnastics was included into the program of the 1896 Summer Olympics, but women were allowed to participate in the Olympics only since 1928. World Championships, held since 1903 also remained for men only until 1934. Since that time two branches of artistic gymnastics have been developing – WAG and MAG – which, unlike men’s and women’s branches of many other sports, are much different in apparatus used at the major competitions, in techniques and concerns.

Women’s artistic gymnastics entered the Olympics as a team event in 1928. At the twelfth (12th) gymnastics World Championships in 1950, WAG as it is known today was included, with competition in team, all-around and apparatus final events, although individual women were recognized in the all-around as early as the tenth (10th) World Championships in 1934. Two years after the full women’s program (all-around and all four event finals) was introduced into the 1950 World Championships, it was introduced into the 1952 Helsinki Games, and this format has remained as such to this day.

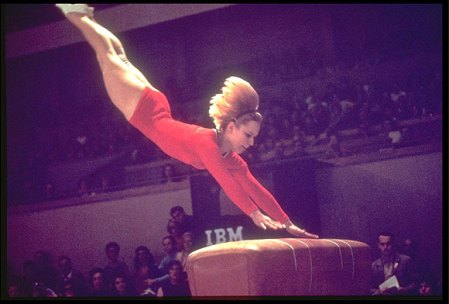

The earliest champions in women’s gymnastics tended to be in their 20s; most had studied ballet for years before entering the sport.Larissa Latynina, the first great Soviet gymnast, won her first Olympic all-around medal at the age of 22, her second at 26 and her third at 30; she became the 1958 World Champion while pregnant with her daughter. Czech gymnast Vera Caslavska, who followed Latynina to become a two-time Olympic all around champion, was 22 before she started winning gold medals.

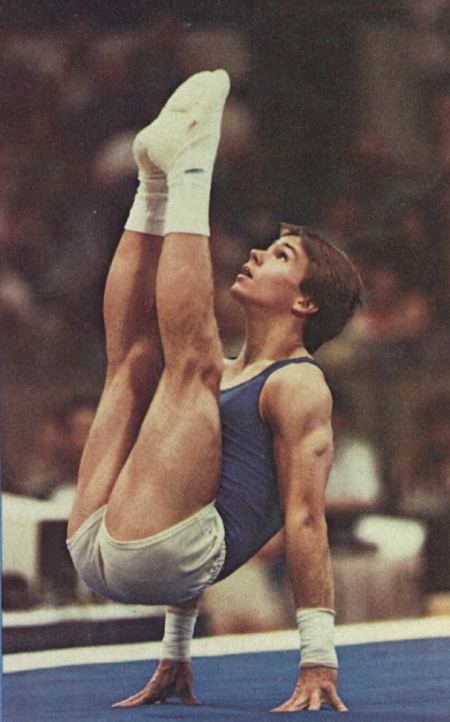

In the 1970s, the average age of Olympic gymnastics competitors began to gradually decrease. While it was not unheard of to for teenagers to compete in the 1960s — Ludmilla Tourischeva was sixteen at her first Olympics in 1968 — they slowly became the norm, as difficulty in gymnastics increased. Smaller, lighter girls generally excelled in the more challenging acrobatic elements required by the redesigned Code of Points. The 58th Congress of the FIG, held in July 1980, just before the Olympics, decided to raise the minimum age limit for major international senior competition from fourteen to fifteen. The change, which came into effect two years later, didn’t eliminate the problem. By the time the 1992 Olympics rolled around, elite competitors consisted almost exclusively of “pixies” — underweight, prepubertal teenagers — and concerns were raised about athlete welfare.

The FIG responded to this trend by raising the minimum age requirement for international elite competition to sixteen in 1997. This, combined with changes in the Code of Points and evolving popular opinion in the sport, have seen older gymnasts return to competition. While the average elite female gymnast is still in her middle to late teens and of below-average height and weight, it is also common to see gymnasts competing well into their twenties. At the 2005 World Championships in Melbourne, the silver medalist on vault, Oksana Chusovitina, was a thirty-year old mother, and she received another silver medal on vault at the 2008 Olympics at the age of 33. At the 2004 Olympics, both the second place American team and the third placed Russians were captained by women in their mid twenties; several other teams, including Australia,France and Canada, had many older gymnasts.

- In 2001 the traditional vaulting horse was replaced with a new apparatus, sometimes known as a tongue or table. The new apparatus is more stable, wider, and longer than the older vaulting horse – approx. 1m in length and 1m in width, gives gymnasts a larger blocking surface, and is therefore safer than the old vaulting horse. With the addition of this new, safer vault, gymnasts are attempting far more difficult and dangerous vaults. Younger gymnasts do not vault onto a vaulting table, though. Younger gymnasts vault onto a mat consisting of cubes of sponge with a slick outside.

During the team qualifying (abbreviated TQ) round, gymnasts compete with their national squad on all four (WAG) or six (MAG) apparatus. The scores from this session are not used to award medals, but are used to determine which teams advance to the team finals and which individual gymnasts advance to the all-around and event finals. The current format of this session is 6-5-4, meaning that there are six gymnasts on the team, five compete on each event, and four of the scores count.

In the team finals (abbreviated TF), gymnasts compete with their national squad on all four/six apparatus. The scores from the session are used to determine the medalists of the team competition. The current format is 6-3-3, meaning that there are six gymnasts on the team, three compete on each event, and all three scores count.

In the all-around finals (abbreviated AA), the gymnasts are individual competitors and perform on all four/six apparatus. Their scores from all four/six events are added together and the gymnasts with the three highest totals are awarded all-around medals. Only two gymnasts from each country may advance to the all-around finals.

In the event finals (abbreviated EF) or apparatus finals, the top eight gymnasts on each event compete for medals. Only two gymnasts from each country may advance to each EF.

Other competitions are not bound by these rules, and may use other formats. For instance, the 2007 Pan American Games had only one day of team competition on a 6-5-4 format, and allowed three athletes from each country to advance to the all-around. In other meets, such as those on the World Cup circuit, the team event is not contested at all.

Before the introduction of the New Life rule, the scores from the team competition carried over into the all-around and event finals, and could have a negative or positive effect on the gymnast’s efforts in subsequent sessions. The gymnasts’ final results, and medal placement, were determined by the combination of scores:

- Qualifiers for all-around and event finals: Team compulsories + team optionals

- Team competition: Team compulsories + team optionals

- All-around competition: Team results (compulsories and optionals) averaged + all-around

- Event finals: Team results (compulsories and optionals) averaged + event final

- Before 1997, the team competition was structured differently. It still consisted of two sessions. However, gymnasts performed compulsory exercises in the preliminaries and their optional routines on the second day. The team medals were awarded on the combined scores of both days. All-around and event final qualifiers were also determined according to the combined scores. In meets where team titles were not contested, such as the American Cup, there were two days of all-around competition: one for compulsories and one for optionals.

The optionals were the gymnasts’ personal routines, developed with their coaches to adhere to the requirements of the Code of Points. They were performed in the team finals, the all-around and the event finals.

The compulsories were routines that were developed and choreographed by the FIG Technical Committee. They were performed on the first day of the team competition. Every single elite gymnast in every single FIG member nation performed the exact same exercises. The dance and tumbling skills of compulsory routines were generally less difficult than those of the optionals, but heavily emphasized perfect technique, form and execution. Scoring was exacting, with judges taking deductions for even slight deviations from the required choreography. For this reason, many gymnasts and coaches considered compulsories more challenging to perform than optionals.

Compulsories were eliminated at the end of 1996. The move was extremely controversial, and many successful gymnastics federations, including Russia, the United States and China, voted against the abolition of compulsories. They argued that the exercises helped maintain a high standard of form, technique and execution among gymnasts. Opponents believed that compulsories harmed emerging gymnastics programs. Many members of the gymnastics community still argue that compulsories should be reinstated.

Many gymnastics federations have maintained compulsories in their national programs. Gymnasts competing at the lower levels of the sport – for instance, Level 4-6 in USA Gymnastics and Grade 2 in South Africa – frequently only perform compulsory routines

- The FIG imposes a minimum age limit on gymnasts competing in international meets. The term senior, in gymnastics, refers to any world-class/elite gymnast who is age-eligible under FIG rules. The term junior refers to any gymnast who competes at a world-class/elite level, but is too young to be classified as a senior. Juniors are judged under the same Code of Points as the seniors, and often exhibit the same level of difficulty in their routines.

Currently, gymnasts must be at least sixteen years of age, or turning sixteen within the calendar year. For the current Olympic cycle, in order to compete in the 2008 Olympics, a gymnast must have a birthdate before January 1, 1993. There is no maximum age restriction.

The one exception to this rule is the year before the Olympics, when gymnasts who are one year shy of the age requirement may compete as seniors at the World Championships and other meets. For instance, gymnasts born in 1988 were allowed to compete in senior events in 2003. This is permitted to allow nations to qualify to the Olympics with their best teams, and to give emerging gymnasts some experience in major competition before the Olympics.

Only senior gymnasts are allowed to compete in the Olympics, World Championships and World Cup circuit. However, many meets, such as the European Championships, have separate divisions for juniors. Additionally, some competitions, such as the Goodwill Games, the Pam Am Games, the Pacific Rim Championships and the All-Africa Games, have rules that permit seniors and juniors to compete together.

The minimum age requirement is arguably one of the most contentious rules in artistic gymnastics, and is frequently debated by coaches, gymnasts and other members of the gymnastics community. Those in favor of the age limits argue that they promote the participation of older athletes in the sport, and that they spare younger gymnasts from the stress of competition and training at a high level. Opponents of the rule point out that junior gymnasts are scored under the exact same Code of Points as the seniors, and train, mostly, the same skills. They also feel that younger gymnasts need the experience of participating in major meets in order to become better athletes; and that if a junior has the skills and maturity to be competitive with seniors, he or she should be allowed that opportunity.

Another point that frequently arises in this debate is the issue of age falsification. Since stricter age limit rules were first adopted in the early 1980s, there have been several well-documented, and many more suspected, cases of juniors with falsified documents competing as seniors. In only one case — that of Kim Gwang Suk of North Korea, who competed at the 1989 World Artistic Gymnastics Championships at the approximate age of eleven — has the FIG taken any disciplinary action.

While the minimum age requirement applies to both WAG and MAG, it is far more contentious in WAG. Most top male gymnasts are in their late teens or early twenties; female gymnasts are typically ready to compete at the international level by their mid-teens.

Scoring at the international level is regulated by the Code of Points. This system was significantly overhauled for 2006. Under the new Code of Points there are two different panels judging each routine, evaluating different aspects of the performance. The A score covers Difficulty Value, Element Group Requirements and Connection Value; and the B score covers execution, composition and artistry. The most visible changes to the Code was the abandonment of the “Perfect 10” for an open-ended scoring system for difficulty (the A score). The B score is still limited to a maximum of 10. The sum of the two provides a gymnast’s total score for the routine. Theoretically this means scores could be infinite, though average marks for routines in major competitions in 2006 generally stayed in the mid-teens.

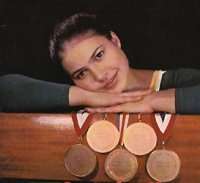

Many gymnasts, including Nadia Comaneci,Mary Lou Retton,Josef Stalder, and Kurt Thomas, have contributed their original skills to the Table of Elements section of the Code that helps define a routine’s difficulty.

Before 2006, every routine was assigned a Start Value (SV). A routine with maximum SV performed perfectly was worth a 10.0. A routine with all required elements was automatically given a base SV (9.4 in 1996; 9.0 in 1997; 8.8 in 2001); it was up to the gymnast to increase the SV to 10.0 by performing difficult skills and combinations.

Many gymnastics insiders, coaches, officials and gymnasts have protested the new Code, with Olympic gold medalists Lilia Podkopayeva,Svetlana Boguinskaya,Shannon Miller and Vitaly Scherbo and Romanian team coach Nicolae Forminte publicly voicing their opposition. In addition, the 2006 report from the FIG Athletes’ Commission cited major concerns about scoring, judging and other points of the new Code. Aspects of the Code were revised in 2007, however, there are no plans to abandon the new scoring system and return to the 10.0 format

- Dominant teams and nations

- USSR / Post-Soviet Republics

USSR , Russia , Ukraine , Belarus: Before the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, Soviet gymnasts dominated both men’s and women’s gymnastics commencing with the introduction of the full women’s program into the Olympics and the overall increased standardization of the Olympic Gymnastics competition format which happened in 1952. They had many male stars such as Olympic All-Around Champions Viktor Chukarin and Vitaly Scherbo and female stars such as Olympic All-Around Champion Larissa Latynina and World-All Around and Olympic Champion Svetlana Boguinskaya who contributed to this tradition. From 1952 to 1992 inclusive, the Soviet women’s squad won almost every single team title in World Championship competition and at the Summer Olympics: the only four exceptions were the 1984 Olympics, which they did not attend, and the 1966, 1979 and 1987 World Championships. Most of the famous Soviet gymnasts were from the Russian SFSR, the Ukrainian SSR and the Byelorussian SSR. Following the breakup of the Soviet Union, Russia has maintained the tradition of gymnastics excellence, medalling at every Worlds and Olympic competition in both MAG and WAG disciplines. Ukraine also has a strong team; Ukrainian Lilia Podkopayeva was the all-around champion at the 1996 Olympics. Belarus has maintained a strong men’s team. Other former republics have been somewhat less successful. In terms of medal results and overall domination, the Soviet legacy remains the strongest of all in Artistic Gymnastics.

Romania: The Romanian team first achieved wide-scale success at the 1976 Summer Olympics with the tremendous success of Nadia Comaneci. Since then, using the centralized training system pioneered by Bela Karolyi, they have been a dominant force in both team and individual events in WAG. With the exception of the defeat of the Soviet women’s team by the Czechoslovakian women’s team at the 1966 World Championships, Romania was the only team ever to defeat the Soviets in head to head competition at the World Championships/Olympic level with their victories at the 1979 and 1987 Worlds. Their women’s teams have also won team medals at every Olympics from 1976 to 2008 inclusive, including 3 victories in 1984, 2000, and 2004. At the 16 different World Championships from 1978 to 2007 inclusive, the women’s team has failed to medal only twice (in 1981 and 2006), and has won the team title seven times including 5 victories in a row (1994 – 2001). With the exception of the 2004 Olympics, they have placed notable gymnasts such as,Daniela SilivasLavinia Milosovici, and Simona Amanar on the Olympic All-Around podium at every Olympics since Comaneci’s success in 1976, and have usually done the same for the individual events at the World Championships, producing World All-Around Champions Aurelia Dobre and Maria Olaru. The Romanian men’s program, while less successful, is still maturing, and producing individual medalists such as Marian Dragulescu at World and Olympic competitions and they have started winning team medals, as well.

United States : While isolated American gymnasts, including Kurt Thomas and Cathy Rigby, won medals in World Championship meets in the 1970s, the United States team was largely considered a “second power” until the mid to late 1980s, when American gymnasts began medaling consistently in major, fully attended competitions. In 1984 the olympic mens team won the gold. The team included Tim Daggett, Peter Vidmar,Mitch Gaylord, Bart Connor, Scott Jonhnson, Jim Hartung, and the team alternate Jim Mikus. In 1991 Kim Zmeskal became the first American World All-Around Champion; the following year at the 1992 Olympics the American women won their first team medal (bronze) in a fully attended Games. Since the breakup of the USSR, the U.S team has become increasingly successful with the 1996 Olympic team victory of the Magnificent Seven in Atlanta, the 2003 Worlds team victory in Anaheim, and a multiple medal hauls in both WAG and MAG at the 2004 Olympics. They have produced individual gymnasts such as Olympic All-Around Champions Carly Patterson (2004) and Nastia Liukin (2008), and World All-Around Champions Shannon Miller (1993, 1994), Chellsie Memmel (2005), and Shawn Johnson (2007). Of particular note is that at the 2005 World Championships in Melbourne, American women won the all-around and every single event final except vault. They continue to be one of the most dominant forces in the sport. The men’s team has also matured, making the medal podium at both the 2004 and 2008 Olympics as well as producing individual gymnasts, most notably World and Olympic All-Around Champion Paul Hamm.

China has developed strong, successful programs in both WAG and MAG over the past twenty five years, earning both team and individual medals. The Chinese men’s team won the team gold at the 2000 Olympics,2008 Olympics, and every team world championship since 1994 except in 2001 when they placed 5th. They have produced such individual gymnasts as Olympic (and World) All-Around Champions Li Xiaoshuang (1996) and Yang Wei (2008). The Chinese women’s team won the team gold medal at the 2006 World Championships and the 2008 Olympics, and has produced individual gymnasts such as Olympic, World and World Cup champions such as Mo Huilan,Kui Yuanyuan,Yang Bo,Ma Yanhong and Cheng fei. Chinese female Olympic individual gold medalists include Ma Yanhong,Lu Li,Liu Xuan, and He Kexin.

-

Japan was largely dominant in MAG during the 1960s and 1970s, winning every team title at every single Olympics from 1960 through 1976 due to individual gymnasts such as Olympic All-Around Champions Sawao Kato and Yukio Endo. Several innovations pioneered by japanese gymnasts during this era have remained in the sport, including the Tsukahara vault. Japanese men gymnasts have re-emerged as a team to reckon with since winning a team gold at the 2004 Olympics. The women have been less successful, however there have been such standouts as Olympic and world medalist Keiko Tanaka Ikeda who competed in the 1950s and 1960s.

The German Democratic Republic, or East Germany, had an extremely successful gymnastics program before the reunification of Germany. Both the MAG and WAG teams frequently won silver or bronze team medals at the World Championships and Olympics.Male gymnasts such as Andreas Wecker and Roland Brucker and female gymnasts such as Maxi Gnauck and Karin Janz contributed to their country’s success. After the reunification of Germany, they have continued to have a measure of success with such gymnasts as Fabian Hambuchen and the former Soviet/Uzbek gymnast Oksana Chusovitina.

The Czechoslovakian women’s team had a very long tradition of success and was the chief threat to the dominance of the Soviet women’s team for decades. They won team medals at every World Championships and Olympics from 1934 to 1970 with the exceptions of only the 1950 Worlds and 1956 Olympics. Among their leaders were the first women’s World All-Around Champion Vlasta Dekanova (1934, 1938) and Vera Caslavska who won outright all (5) European, World and Olympic All-Around titles during an Olympic cycle from 1964 to 1968 – a feat never matched by any other gymnast (male or female). Caslavska also led her teammates to the world team title in 1966, making the Czechoslovakians one of the only two countries’ teams (the other being Romania’s) to ever defeat the Soviet women’s team at a major competition. Although their men weren’t as successful as a team, they were still noteworthy and did produce 1907 World All-Around Champion Joseph Czada who was a continuous presence at World Championships for years to come.

Another Eastern Bloc country whose women achieved notable results was Hungary. Led by individuals such as 10-time Olympic medalist (with 5 golds)Agnes Keleti, their team medaled at the first 4 Olympics with women’s artistic gymnastics competitions (1936 – 1956) as well as at the 1954 World Championships. Their women’s program went into a decline with minor occasional success, although much later during the late 1980s and early 1990s, World and Olympic Vault Champion Henrietta Onodi put them back on the map.Their men never had quite the same level of success as their women, although Zoltan Magyar dominated the pommel horse event during the 1970s, winning 8 (of a possible 9) European, World and Olympic titles from 1973 – 1980. World and Olympic Rings Champion Szilveszter Csollany also kept Hungary on the medal platform at major competitions for a decade starting in the early 1990s.

The Italian men’s team won the Olympic title at every games from 1912 to 1932 with the exception of 1928, when they placed 5th. Led by Olympic All-Around Champions Alberto Braglia (1908, 1912),Giorgio Zampori (1920), and Romeo Neri (1932), theirs was a legacy that far surpassed all others in this Olympic discipline until the arrival of the USSR in 1952. In later years, Yuri Chechi would become several-time World and Olympic rings champion (mostly during the 1990s), and their women’s program served notice to the rest of the world that it had arrived as Vanessa Ferrari took the all-around titles at both the World Championships in 2006 and European Championships in 2007.

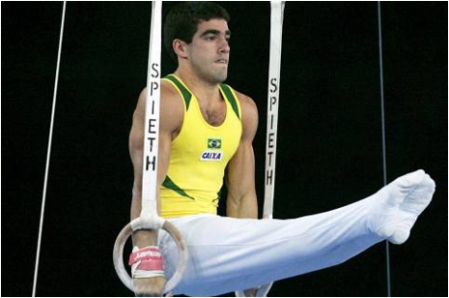

Several other nations were at one time or have become in recent years serious contenders in both WAG and MAG. Part of the rise of the success of various countries’ programs in recent years is attributable to the exodus of lots of talent from the USSR and other former Eastern Bloc countries. Korea, Canada, Spain,Australia, Brazil, France and Great Britain, among other countries, have produced Worlds and Olympic medalists and have started winning team medals at the European, World, and Olympic level.

- Rhythmic gymnastics is a sport in which single competitors or pairs, trios or even more (generally five) manipulate one or two apparatus: rope,hoop ,ball,clubs and ribbon. Rhythmic Gymnastics is a sport that combines elements of ballet,gymnastics, theatrical dance, and apparatus manipulation. The victor is the participant who earns the most points, as awarded by a panel of judges, for leaps, balances, pivots, flexibility, apparatus handling, and artistic effect.

The governing body, the Federation Internationale de Gymnastique (FIG), changed theCode of Points in 2001, 2003 and 2005 to emphasize technical elements and reduce the subjectivity of judging. Before 2001, judging was on a scale of 10 like that of Artistic Gymnastics. It was changed to a 30-point scale in 2003 and in 2005 was changed to 20. There are three values adding up to be the final points—technical, artistic and execution.

International competitions are split between Juniors, under sixteen by their year of birth; and Seniors, for women 16 and over again by their year of birth. Gymnasts typically start training at a very young age and those at their peak are typically in their late teens or early twenties. The largest events in the sport are the Olympic Games, World Championships, and Grand-Prix Tournaments.

- Rhythmic gymnastics grew out of the ideas of I.G. Noverre (1722–1810), Francois Delsart (1811–1871), and R. Bode (1881), who all believed in movement expression, where one used dance to express oneself and exercise various body parts.Peter Henry Ling further developed this idea in his 19th-century Swedish system of free exercise, which promoted “aesthetic gymnastics”, in which students expressed their feelings and emotions through bodily movement. This idea was extended by Catharine Beecher, who founded the Western Female Institute in Ohio, United States, in 1837. In Beecher’s gymnastics program, called grace without dancing, the young women exercised to music, moving from simple calisthenics to more strenuous activities. During the 1880s, Emil Dalcroze of Switzerland developed eurhythmics, a form of physical training for musicians and dancers.George Demeny of France created exercises to music that were designed to promote grace of movement, muscular flexibility, and good posture. All of these styles were combined around 1900 into the Swedish school of rhythmic gymnastics, which would later add dance elements from Finland. Around this time, Ernest Ilda of Estonia established a degree of difficulty for each movement. In 1929, Henrich Medau founded The Medau School in Berlin to train gymnasts in “modern gymnastics”, and to develop the use of the apparatus.

Competitive rhythmic gymnastics began in the 1940s in the Soviet Union. The FIG recognized this discipline in 1961, first as modern gymnastics, then as rhythmic sportive gymnastics, and finally as rhythmic gymnastics. The first World Championships for individual gymnasts took place in 1963 in Budapest,Hungary. Groups were introduced at the same level in 1967 in Copenhagen ,Denmark. Rhythmic gymnastics was added to the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, with an Individual All Around competition. However, many federations from the Eastern European countries were forced to boycott. The Canadian Lori Fung was the first rhythmic gymnast to earn an Olympic gold medal. The Group competition was added to the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, Georgia.

Posted by mandyricee

Posted by mandyricee